Nurtured by low interest rates over the past few years, second-lien lenders have been effortlessly swiping deal flow from mezzanine and high-yield bond underwriters.

Now, with interest rates on floating-rate loans creeping higher, and the market growing nervous about how second-lien lenders will react in a downturn, the tables are turning. The sprinting second-lien juggernaut is finally meeting solid resistance from the debt providers it had once so hastily pushed aside.

Interest rates are not yet high enough to push second-lien completely out of favor. So to take matters into their own hands, mezzanine and high-yield providers have been employing creative twists on their classic debt structures. Mezzanine firms, for example, are promoting the use of holding companies to issue debt, rather than the underlying portfolio companies themselves, as an advantageous way to add leverage; high-yield bond underwriters have been touting private placements as a way for portfolio companies to avoid the regulatory burdens of having publicly-registered securities trading hands.

For sponsors, the result of this creativity and competition has been a sort of financial-engineering Golden Age where they have more options than ever when it comes to how they finance their transactions. Today, general partners in the small, middle and large markets can opportunistically toggle between mezzanine, second-lien and high-yield bonds to meet their subordinated debt needs. Those with the best lender relationships can use them to out-lever their rivals, and therefore outbid them at auction.

“It’s pretty much an ‘either or’ market for borrowers looking to tranche up today,” says John Fruehwirth, managing director of Washington, D.C.-based business development company

Mezz Turning Point

In the small and middle markets, the choice for sponsors is often between mezzanine and second-lien.

Mezzanine debt is an unsecured, fixed-rate product, often involving equity kickers, that’s subordinated to second-lien debt (and other senior secured debt) but senior to high-yield bonds. Second-lien debt, on the other hand, is a secured, floating-rate product that falls below first-lien debt in the capital structure, but sits above all the unsecured debt below it.

Years ago, all was well and good for mezzanine firms. With the high-yield bond market available only to the big guns, small and mid-market buyout firms often had no where else to turn but mezzanine debt to fill in gaps in their capital structures.

That changed a few of years ago, however, when LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) sunk to the 2% to 3% range and interest rates fell accordingly. Second-lien lenders—many of them hedge funds—gleefully crashed the market, charging LIBOR plus 8% interest for their paper, which gave way to rates as low as 10% or 11%. The interest rates on mezzanine debt, by contrast, were still hovering around 14%.

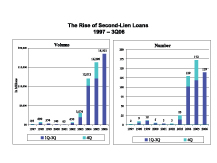

The predictable result was a sharp fall in the use of mezzanine and a spike in the issuance of second-lien debt. The numbers are clear. Prior to 2003, there had never even been more than $700 million of second-lien debt issued in a single year, according to Standard & Poor’s Leveraged Commentary and Data. But as of Q3 2006, more than $18.5 billion in second-lien has already been issued, eclipsing last year’s $16.2 billion total.

But mezzanine firms have begun to mount a comeback. Today, with LIBOR sitting between 5% and 5.5%, second-lien loans are being priced on average between 12% and 14%—cutting into the pricing advantage it held over mezzanine, Allied Capital’s Fruehwirth says. Moreover, as talk of an impending market correction continues, some sponsors have grown wary about how second-lien lenders, who have not been around long enough to go through a down market, will behave once companies fall into default on their loans or land in bankruptcy court.

“The issue is really about who’s providing the second-lien and how the lender’s structure impacts their work-out strategies in the event of a troubled situation,” says John Brignola, a partner and co-founder of

As such, a number of private equity firms have started reassessing their options when it comes to junior lending structures. “We’re very much a relationship-focused firm, and most of our long-term relationships are with mezzanine lenders,” says one mid-market general partner. “We know how they work in sideways situations and we like to work with what we know.”

Stephen Boyko, a partner at law firm Proskauer Rose LLP and co-head of its Junior Capital Group, says that attitude is becoming more common. “Today we’re seeing a lot more mezzanine term sheets coming across our desks than we were six months or a year ago,” he observes. “Some people are getting disenchanted with second-lien credit structures in light of the increase of LIBOR and interest rates. But having said that, we have not seen a slowdown in the amount of second-lien term sheets coming our way either.”

It’s clear, however, that mezzanine lenders are ready to take the wheel after years of being in the backseat. As of the close of the third quarter, more than $14.8 billion in mezzanine capital had been closed on by fund-raisers, almost double the $7.9 billion raised in the same period last year.

Getting Creative

Beyond simply raising larger investment vehicles, mezzanine lenders have been getting more creative with the structures of their loans, both to watch there own backs, as well as to better serve the needs of their clients.

“There are so many smart lenders out there who have come up with dynamic multi-tranche strategies and, within that, mezzanine has morphed into various types of different securities, including unsecured mezzanine and secured mezzanine with silent second-liens,” says Proskauer Rose Partner Steven Ellis, who serves as co-chair of the firm’s Corporate Finance Group.

For the uninitiated, a silent second-lien is a lien that is stripped of its secured creditor rights (hence silent) and is tacked onto an unsecured debt product. Some mezzanine lenders use it as a tool to give themselves a leg up over other unsecured and/or trade creditors, as the lien component elevates them in the capital structure. Other than stepping the mezzanine lender up a notch in the capital structure, the lender has the same rights a traditional mezzanine player.

The “holdco” note is another security that’s finding its way more and more into mainstream products, Ellis says. Holdco notes differ from traditional mezzanine debt in that, rather than being placed at the operating company level, it is placed on the parent, or holding company level. There it is one step removed from the assets and revenues of the company, and it is therefore more equity-like. Sponsors use holdcos as a way to layer on more financing while keeping the stress of additional leverage away from the operating company.

Returns tend to be higher for the lender of holdco notes than for traditional mezzanine debt because it’s a riskier investment, one expert says. Terms, too, tend to be more borrower-friendly, as covenants are generally looser; whereas borrowers might break covenants on mezzanine debt for being 10% off management’s plan, for holdco notes it is more like 20% off. And oftentimes holdcos will have a bigger PIK (pay in kind) component than traditional mezzanine.

Junk Bonds Go Private

Upstream, second-lien lenders appear to be driving the same level of competition and ingenuity that they are in the middle market.

“In the larger transactions, there may have been some issuance displacement in the high-yield bond market by the broadly-syndicated second-lien market, which some viewed as more attractive because of lower call premiums and ease of execution,” LBC Credit Partners’s Brignola says.

To be sure, whatever scalable displacement there’s been has not put a big dent in the popularity of high-yield bonds. As of Oct. 12, $91.59 billion in junk bonds had been issued since the beginning of this year, a number that’s closing in on 2005’s year-end total of 93.45 billion, according to S&P LCD. And there’s no end in sight to the market’s bull run. The default rate for U.S. speculative-grade bonds for the year ended Sept. 30 stood at a mere 1.5%, the lowest it’s been since April 1995, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

That said, some extremely large second-lien deals have come to market. Among these is the proposed $33 billion buyout of HCA Inc. by

“From an issuer’s perspective, this development is a favorable one,” says Ian Blumenstein a partner in Proskauer Rose’s Corporate Department. “It used to be that high yield was the only source of financing for large-cap transactions, and that if [an issuer] couldn’t price an offering that was pretty much the death knell for the deal. But now they have options. Investors today will test the waters in the high-yield market, and if they don’t like what they see, they’ll go to the second-lien market.”

He adds that part of the allure of large second-lien loans is that they do not have to comply with Sarbanes-Oxley since they don’t eventually get released to the public market.

To compete, high-yield’s answer to the more-private second-lien is what Blumenstein calls the “144A-for-life-deal,” which is named after the Securites and Exchange Commission’s Rule 144A, which permits privately placed securities to be traded among qualified institutional buyers.

Typically, high-yield debt is issued with registration rights that require the issuer, six months to a year after a bond deal is closed, to exchange the privately placed bonds for publicly registered bonds. And while high-yield investors like registration rights because they lead to a level of SEC oversight, the downside for issuers is that once they register the bonds with the SEC, they must comply with SarbOx.

With a 144A-for-life deal, the loan is syndicated by investment banks in the traditional way, but it is sold without registration rights. The bonds can still trade in the private market among institutional investors, but cannot be traded publicly, Blumenstein says.

The downside to a 144A-for-life deal is that issuers typically have to pay a premium in the form of a higher interest rate—generally 25 to 50 basis points higher—because of the impact the private offering has on liquidity.

“Many issuers have concluded that the premium is worth paying in order to avoid the costs of SarbOx compliance. However, the fact that there is the premium may make second-lien or mezzanine more attractive,” Blumenstein says.

Regardless of the kind of security, there’s no doubt that the junior lending market is matching the growing sophistication of the private equity asset class, and that that sophistication is being driven by competition and experience. The result is that buyers today have more freedom when it comes to how they structure their deals. The catch, however, is that freedom comes with a price tag.

“The ability to pick and choose debt is helpful, but I don’t think it’s going to have a positive impact on long-term returns because the borrowers are the ones who are ultimately paying for that choice,” says Terry Mullen, a managing director at New York-based

If you do not receive this within five minutes, please try and sign in again. If the problem persists, please

email:

If you do not receive this within five minutes, please try and sign in again. If the problem persists, please

email: