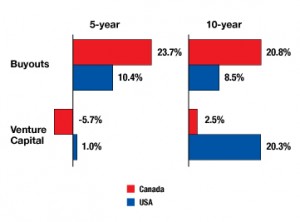

In size and activity, the buyout market in the United States is far more impressive than that of its Canadian counterpart. But it’s behind in one crucial area: returns.

Five-year net returns for Canada-based buyout funds, through June 2006, weighed in at 23.7 percent, nearly 3.5 times more the net five-year return of 6.8 percent for U.S. buyout funds during the same span, according to the “Private Equity Canada 2006” report published by consulting firm McKinsey & Co. Adding another five years to the return horizon still leaves the U.S. buyout market in the dust. Ten-year returns of 20.8 percent in Canada blew away the corresponding 9.5 percent returns generated by U.S. firms, according to the report, which relied on Thomson Financial, publisher of Buyouts, for some of its data.

One possibility for the difference could well be the far smaller population of Canadian buyout firms—dozens, compared with hundreds of U.S. buyout shops. McKinsey consultants and buyout professionals familiar with both markets also suggested a host of other explanations for the discrepancy, including that Canadian companies are cheaper to buy, relatively speaking. The average purchase-price multiple for Canadian companies generating EBITDA of at least $1 million and acquired in LBOs between 2002 and 2006 came in at 6.2 EBITDA, McKinsey found. In the United States, the comparable figure was 9.3x EBITDA.

Why do Canadian companies come cheaper? The report, which supplemented its findings with surveys and interviews with deal professionals from Canadian firms such as

Fewer auctions, and less competition for deals is also a factor, although that’s beginning to change, said Peter Gottsegen, a managing director and founding partner of

Still another explanation for Canada’s return supremacy may be the uniquely Canadian phenomenon of income trusts. In their heydays, these TSX-listed entities—largely exempt from income taxes and fat with cash—were able to offer valuations between 30 percent and 40 percent higher than what a strategic buyer or LBO shop could pay. So buyout firms were able to buy low and sell high to income trusts, or even take their companies public as an income trust.

Income trusts enjoyed their cash cow status because they were allowed by the Canadian federal government to pay out their cash distributions to unit holders before income tax on their earnings was calculated. “If you sold something into the income trust market, you got a big fat valuation as a result,” one buyout professional noted. “There was one time that, after speaking to two strategic acquirers, we were able to get an extra turn and a half [of EBITDA] just by being able to sell it into the income trust market.”

Unfortunately, that exit opportunity is largely gone. Last October, the Canadian federal government said that after 2011, income trust earnings will be taxed at a rate of about 20 percent prior to distributions—effectively reducing the amount unit holders will receive. One result has been a parade of Canadian income trusts being taken private. If Canadian buyout shops can find a way to cash in on these deals they may well continue to outperform their colleagues in the United States.—A.N.

If you do not receive this within five minutes, please try and sign in again. If the problem persists, please

email:

If you do not receive this within five minutes, please try and sign in again. If the problem persists, please

email: