Now, however, interest rates are beginning to buck higher as the Federal Reserve has signaled that it plans to taper off its massive bond purchases that pushed long-term rates to historic lows. Even so, providers of sub debt may continue to find the environment hostile, the result of regulatory reform and an evolution in the marketplace that have brought new competitors to the field of leveraged finance.

“This is a structural change,” said Ronald Kahn, a managing director at Chicago investment bank Lincoln International LLC. “Mezzanine works best with a true senior bank-loan market.” But as a result of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law, commercial banks have retrenched from leveraged lending, an area of finance that is seen by regulators as being particularly fraught with risk.

Other players in the market disagree, arguing that the current crunch against subordinated debt is at least partly a cyclical phenomenon, the result of a unique collapse in credit markets during the financial crisis, followed by an extended period of uncommonly low interest rates.

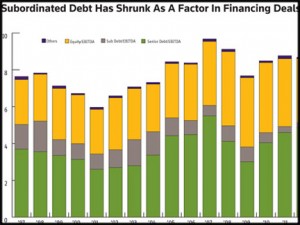

Whatever the case, subordinated debt has to a large degree been pushed out of the capital stack, a pattern that began perhaps as long ago as 2004, when the mid-decade buyout boom was still in full swing, according to data from S&P Capital IQ Leveraged Commentary & Data. The use of subordinated debt peaked in 2003, when subordinated lenders would provide 1.42 turns of leverage for such credit, at a time when deal pricing was more than 7x a borrower’s EBITDA, according to LCD.

While pricing would continue to rise for four more years, peaking in 2007 at 9.7x EBITDA, subordinated debt was already in decline, representing less than six-tenths of a turn of leverage that year, LCD reported, and its role has only continued to diminish, bumping higher in the recession year of 2008 at eight-tenths of a turn but then resuming its fall, to 0.27 turns of EBITDA last year.

In the middle market, in contrast to the larger corporate market, the pattern has been the same, although the swings have been less volatile. LCD, which defines the mid-market as comprising companies with less than $50 million of EBITDA, found that the use of subordinated debt in that segment also peaked in 2003, albeit at a more modest nine-tenths turns of EBITDA, and it has declined more moderately. Last year, LCD reported, subordinated debt still represented three-quarters of a turn of EBITDA for mid-market deals.

‘Generational Shift’

Part of the reason could be the broader evolution of the buyout business, where conventional forms of subordinated debt, such as mezzanine finance, have come under pressure as the economics of the industry have changed. “It’s a generational shift,” argued Theodore Koenig, the president and chief executive officer of Monroe Capital LLC, a Chicago finance company that provides senior secured and junior secured debt to mid-market companies. “Mezzanine historically has enjoyed what would be considered equity returns today. It’s a function of the yield requirements.”

In the past, subordinated debt promised investor returns in the mid- to upper teens, while returns to private equity sponsors approached 30 percent. Today, top-quartile equity returns are more like 20 percent, so that the kinds of returns once delivered by mezzanine are now going to the equity part of the capital stack. At the same time, senior debt used to provide a return in the high single digits or low double digits, but with low interest rates since the financial crisis, senior debt is now bringing returns in the mid single digits, or even lower, Koenig said. “Sub debt has been subject to this massive squeeze.”

Following the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve stepped in with a massive bond-buying program known as quantitative easing, which has held interest rates low and made it more difficult for subordinated lenders to achieve their earnings goals for their investors.

In addition, new entrants have discovered the market, such as business development companies, which typically seek to deliver a return to their investors in the high single digits. St. Louis-based investment bank Stifel Nicolaus & Co. tracks a universe of 38 publicly traded BDCs, 23 of which have been formed in 2007 or later.

“BDCs were unheard of 10 years ago, but they have stepped in and filled the vacuum,” said Koenig, whose company launched its own BDC vehicle, Monroe Capital Corp, last October.

Likewise, the emergence of unitranche financing has put additional pressure on mezzanine, lenders say. Unlike conventional senior-subordinated capital arrangements, lenders can present unitranche deals to borrowers at a single, blended interest rate (although lender relationships may be more complex behind the scenes), while eliminating the inter-creditor agreements that can cause difficulties in bringing a deal to close. But unitranche is generally more useful for smaller deals, because the strategy is not suitable for broadly syndicated loans, such as the ones that LCD tracks for its analyses.

Other forms of less-senior debt also seem to be holding their own in a shifting loan market. Second-lien secured loans remain popular, lenders report, typically in a structure where the first-lien loan is secured by a borrower’s receivables and inventory, and the second lien is secured by the borrower’s other assets.

Second-lien, despite the name, counts as senior debt so long as it is secured by assets of the borrower. LCD counts secured seconds as senior loans, although Kahn of Lincoln International said such borrowers may represent larger risks than their lenders acknowledge. “There is not even close to collateral coverage, but they call it a senior loan.”

To be sure, subordinated debt deals are still getting done. During a single week in June, Babson Capital Management LLC announced two such deals, both featuring equity co-investments. Babson Capital, the Boston-based leveraged finance unit of Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co., said it participated in Main Street Capital Holdings’s acquisition of the Hi-Rel Group LLC, a maker of metal components for microelectronic packaging, and in High Road Capital Partners’s acquisition of The Crown Group Inc, a maker of industrial coating equipment. But Babson Capital did not describe the financial arrangements, including even the overall value of the transactions. Both Main Street Capital and High Road Capital focus on the lower end of the middle market. Babson Capital declined to make executives available to comment for this story.

Cyclical Or Structural?

Defenders of subordinated debt argue that the pressure on junior loans represents a simple cyclical squeeze. One capital market expert at a mid-market buyout shop compared the current environment to 2006 and 2007 during the peak of the buyout boom, when credit markets were roaring and lenders were competing based on their lower cost of capital. In such a market, which he said that then, as today, with markets awash in liquidity, lenders are willing to accept lower returns.

Given such challenging conditions, what is a mezzanine lender to do? “You pull in your horns and wait,” said David D. Buttolph, a managing director, founder and co-manager of Brookside Mezzanine Partners in Stamford, Connecticut. “The lenders start taking risks and not getting paid for it.”

Brookside Mezzanine, which specializes in restaurants, health care, manufacturing and services companies across the United States, targets companies with EBITDA of $5 million to $20 million, most of them backed by financial sponsors, in which Brookside typically provides subordinated debt with an equity kicker often in the form of a co-investment, Buttolph said. “We do a lot of smaller deals, and then we grow them through acquisitions.”

The first part of the year has been slow, Buttolph said, which he attributed to dealmakers pulling transactions into the last part of 2012 ahead of anticipated tax increases. But Brookside Mezzanine, which has raised more than $500 million through three funds dating from 2001, benefits from having very patient capital behind it; the firm’s three funds, structured as small business development companies licensed by the Small Business Administration, can obtain long-term financing for its lending through the SBA’s SBIC debenture program.

“The days of low, flat rates are starting to end,” Buttolph said. And although he said he doubts that higher rates will impact the market too greatly, he warned that rising rates could be a threat to lenders who may have branched into riskier areas, such as subordinated debt, where they may not have the expertise to manage risks as the market turns. “When they start having mission creep, they get into trouble.”

If you do not receive this within five minutes, please try and sign in again. If the problem persists, please

email:

If you do not receive this within five minutes, please try and sign in again. If the problem persists, please

email: